I am often on the lookout for opportunities to spark my drawing practice. Sometimes it’s just a matter of keeping my eyes open. On this day, I was heading into the school from the parking lot to teach a class on ink drawing one chilly dawning morning in late November. A gnarly tangle of bent branches and twigs caught my eye at the base of the Burdock trees that border the lot. The so-called invasive species trees harbour hundreds of robins in winter who enjoy the plentiful berries.

Places we rarely stop and notice: parking lots, bus stops, subway platforms, spaces we associate with passing through, can reveal something if can be present to them.

Instinctively, I paused and reached into the thicket, breaking off several short, spikey twigs, and pricking my cold fingers on the sharp kinks. I had been looking for something different for my students to draw with. To reinvigorate figure drawing that day and get us out of the routine.

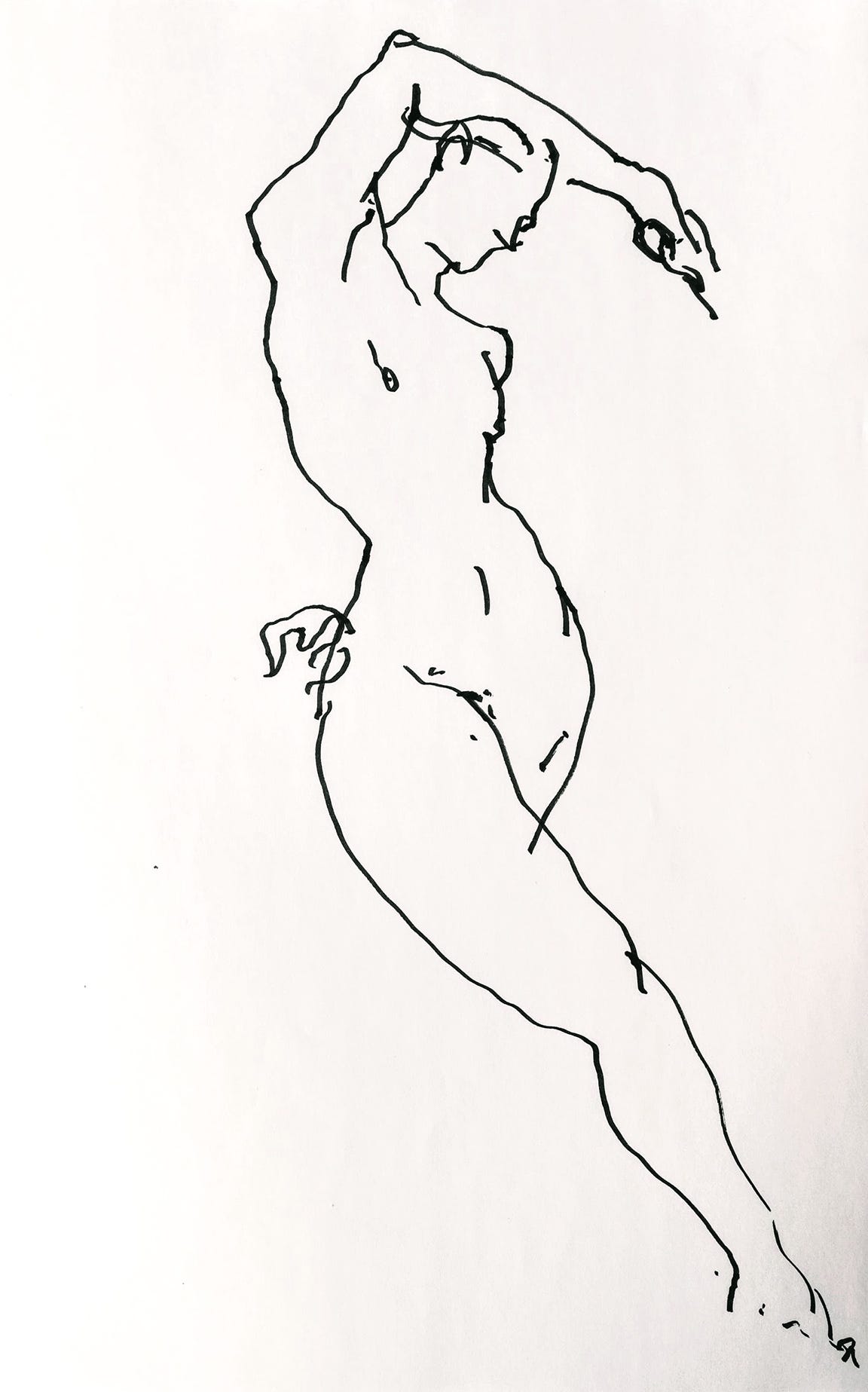

Soon after, in class, students took the short twigs and cups of India ink with curiosity. They drew the model’s lyrical and dynamic sequence of short poses with great concentration and didn’t seem at all inconvenienced by the primitive yet elegant medium they were now discovering. I could see that they were engaged in a special kind of flow, capturing the models’ graceful gestures with the parallel gestures of their twig-clutching hands. They covered the pages with inky, calligraphic figures consisting of agitated, twig-like lines. In the process, cups of ink were spilled, resulting in furious impromptu cleaning committees.

Branching Out

I had to give it a try. Grappling with the twig, I felt strangeness and some strain in my hand and I had to hold it with an unfamiliar grip. Paradoxically, I found that drawing gesturally felt easier, more intuitive. There was a rush of feeling in finding a new voice to speak. The contours that fishtailed naturally as the twig whiplashed gently across the page with each stroke seemed to express the essence of the model’s dance-informed poses.

I was reminded of Paul Klee’s concept of drawing being ‘taking a line for a walk.’ Except, in this case, it was a meandering line that needed to be kept on a long leash. The line darted, scurried, and sometimes chased its own tail, never completely straying from the path.

My hand now became accustomed to the twig that at first felt awkward. The strangeness of it still brought my attention to my hand as I drew. However, an easy curiosity diffused my everyday tendency towards performance and excessive concern with skill and notions of the ‘right’ way to draw. This distracted me from what was happening on the page. Ted Baylis in ‘Art and Fear’ writes that “imperfection is not only a common ingredient in art but very likely an essential ingredient. Ansel Adams, never one to mistake precision for perfection, often recalled the old adage that, “the perfect is the enemy of the good.” His point being that if he waited for everything in the scene to be exactly right, he’d probably never make the photograph.”

Twig art takes the expressive and accidental to another level. Dip the unique point of the twig into the ink and lay down a line. The line starts out bold and then trails off to a scratch inches later. With each dip, the stroke changes. As the strokes go swiftly onto the page, you are both instigator and witness to the act of drawing. There are no corrections and there is little room for hesitancy. The lines of a drawing can be said to be the traces left behind by an artist’s gaze, which is searching out the subject before his eyes (John Berger). Twig sketching creates an opening, a space where I can choreograph the lines with spontaneity, create fresh arrangements upon the page and capture a charged moment in time.

Here’s another part of the story. I drew a lot when I was a kid, long hours of drawing professional athletes from photos and cartoons in the style of Peanuts and Mad Magazine. Growing up in an artistic household, my early experience of drawing constantly, and at any time of the day, defined me in many ways. A wealth of art supplies were around and available to me, drawers of sharpened pencils, and half-finished sketchbooks (my father had a habit of covering ten or so pages, abandoning the sketchbook and starting a new one.) It is just possible some of my present-day curious fixations with drawing implements of any kind, are buried in childhood experience.

Drawing the human figure is hard. But there can be moments of ease in the process and we can invite them through the tool we choose to draw with on any given day. We can learn from these moments. We tend to discount the ease and pleasure of drawing, not believing in the value of it, with a tendency to try too hard. Bringing inappropriate effort into drawing clouds our ability to perceive what we are drawing and receive fresh insights.

An experience such as this, drawing a model with a simple broken stick, contains several pieces: a focus of observation and interpretation, the exercise of skill and the novelty of exploration absolutely simultaneously.

And it’s not like It hadn’t occurred to me to sketch with a twig, branch, stick, or a tree. I was looking for something that could produce the fluid, messy and sublime strokes of Rembrandt and Van Gogh.

Humans have been drawing with sticks and twigs from time immemorial. Ancient animal drawings that cover the surfaces of the great cave art ‘galleries,’ were created with sticks as well as brushes. What is more natural than picking up a stick and drawing in the wet sand? Vine and willow charcoal are essentially just charred sticks. In recent memory, there is a rich history of ink drawing with steel dip pens, reed pens, and quill feathers. The liveliness of Master reed pen drawings by Rembrandt makes it seem as if they were sketched just yesterday. Rembrandt’s presence lives on in lines that seem to unspool inevitably onto the page from his inked-stained hand. Some are elegant and some are rough and blotchy. The reed pen is a direct extension of his hand, mind, and heart.

Days later, walking in the ravine, I spotted some tall grasses with bamboo-like stalks. I cut a few down and made my own version of reed pens from the grasses. They resulted in wonderful drawing tools and in further exciting figure drawing experiences.

Love this lots.

Fun article – Looking forward to experimentation with reed pens! Heather